|

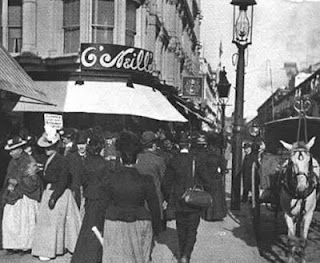

| Intersection near Skidmore House (4th and Bowery) - 1907 |

The landmark Skidmore House at Bowery and 4th Street is one of the last vestiges of the Bowery's vivid past. The Bowery area was America's most notorious skid row in the early 19th century, frequented by the city's most prominent derelicts - prostitutes, drunkards, vagrants, etc. The Encyclopedia of New York City notes that early in the twentieth century the Bowery was such an infamous place of squalor, alcoholism, and wretchedness that even prostitutes gravitated to other neighborhoods. "No other skid row in the United States attracted so many vagrants or so much notoriety." Also distinct of the area was the above-ground train tracks above the Bowery that have since been taken down.

|

| Skidmore House - 2013 |

Thankfully, the Bowery area has entered a resurgence in the last decade and is one of the city's most desirable rental areas. Built in 1845, the Skidmore House is a Greek-revival townhouse that was formerly home to dry goods merchant Samuel Tredwell Skidmore (1801-1881), his wife Angelina, and their eight children. When the Skidmore's moved into the "Bond-street area" as it was called at that time (now it's called "NoHo"), the area was one of the wealthiest in the city. For example, when Charles Dickens visited Manhattan in 1842, he was entertained at the townhomes across the street according to the New York Times.

Samuel's cousin Seabury Tredwell lived four houses down at what has been turned into the Merchant Museum, the only perfectly preserved 19th century townhome in the city according to the museum. When Samuel climbed the 8 steps from street level to the townhome's entrance back in the nineteenth century, he was greeted by his wife and 8 children. Like many townhomes of the period, the Skidmore house contains a "jewelbox" area between the outside door and the door into the house. It was here that guests would announce themselves and wait to see whomever they were calling on. The ground floor was likely used by the Skidmore's for their day-to-day living. The fourth floor, the top floor of the building, was likely a servant's quarter and storage attic. The Tredwell house four doors down employed four female servants that worked for around $3/month, according to the staff at the Merchant House. The Skidmore family likely used the first floor for welcoming guests to dinner parties or social gatherings. "Sociables" were common at the time and Samuel Skidmore frequently wrote about them in his diary:

"April 28, 1858. I hurried home as I had to go to a confounded 'Sociable' at the Tredwells'. Ben & I went in about 9 1/2 PM. Not a great many there. The evening was decidedly stiff but on the whole passably good for a 'sociable.'"

Samuel Skidmore died in the townhome in 1881 and the family subsequently left the townhome in 1883. At this time, the once-coveted area around the Bowery had fallen into disarray where it remained for most of the twentieth century.

|

| Skidmore House (right) and Merchant Museum (left) - 2004 |

The Landmark Preservation Committee awarded the Skidmore House landmark status in 1970 describing it as "unusually impressive." Little is known about what happened to Skidmore House from 1883-1970, but the staff at the Merchant's Museum said it was likely rented to various people. The ground floor is said to have been rented by the Alpha Mu Sigma fraternity of Cooper Union from 1962-1965 until a fire displaced the fraternity and seriously damaged the building. Skidmore House fell into extreme disarray in the latter half of the twentieth century with the roof actually imploding around 2004. During this period, the house is said to have been occupied by vagrant squatters who stole some of the building's unique features, including a charming "Skidmore" bell that once adorned the building's façade, according to the staff at the Merchant House. The Landmark Preservation Committee sued the building's owner, and in 2004 won a Court order that the building be repaired.

|

| Skidmore House's neighboring rental building (2 Cooper) and its pool |

The building was subsequently leased to a development group that committed to repairing the building in exchange for a favorable zoning ruling that allowed it to build a 134 unit condo building next door. In 2011, the building's interior was gutted and 10 apartment rental units - all unique to each other - were built. In 2013, an average one bedroom rented for about $4500/month for roughly 500 square feet. But the best perk of all was that all residents of Skidmore House are entitled to use the amenities in the neighboring 2 Cooper high rise apartment building. 2 Cooper includes a pool on the top floor with 360 degree views of the city. It is arguably the best pool in all of Manhattan.

|

| The pool scene at 2 Cooper on a hot summer day in 2013 |

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)